Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Music at Jimmy Carter’s White House

“Country music is part of the soul and conscience of our democracy. It unfolds the inherent goodness of our people and our way of life. It captures our indomitable spirit and pulsates with the sorrows, joys, and unfailing perseverance of ordinary men and women who sustain our national vitality and strength.”1 – Jimmy Carter at the Country Music Association Concert at the White House on April 17, 1978.

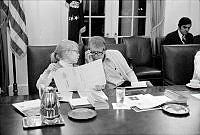

Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris visit Jimmy Carter at the Oval Office in 1977. Credit: The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and MuseumIn 1976, when Americans elected Jimmy Carter to the presidency the nation was dealing with economic downturn, rising crime, urban decline, and above all the aftermath of Watergate. Instead of being cynical about these challenges, Carter said in his nomination speech, “We have in America a nation that, in Bob Dylan’s phrase, is busy being born, not dying.”2 Carter’s country, jazz, blues, classical, and gospel concerts at the White House sought to bring people together. Carter saw music as a moral force, which could heal America after an era of strife, division, and scandal. More than passing a bill or making a speech, a good concert could help inspire feelings of reconciliation and unity. President Carter used music for political purposes, like fund-raising for elections, winning the youth vote, distinguishing himself as an outsider, providing networking opportunities for his administration, promoting diversity, and creating peace between nations. President Carter and First Lady Rosalynn Carter also saw music as a universal language that could promote healing nationally and internationally. They believed the power of music could foster racial equality and promote world peace.

The Carters and Music

The Carters applied music to these problems in part because it was meaningful to their personal lives. Jimmy Carter is not a musician. In sixth grade, music was the only subject in which he did not earn an “A.”3 But he loves music. As a devout Christian Sunday school teacher, it is a part of his religious identity. “Amazing Grace” and “Eternal Father Strong to Save” are among his favorite songs.4 Yet he is as much at home attending a rock concert as he is listening to a choir. He is a fan of virtually every genre, especially classical, jazz, country, and rock.

During his first month in office, Carter installed a high-fidelity sound system in the inner White House office. He wrote in his diary that, “for eight to ten hours every day I listen to classical music.” The president tasked his personal executive secretary, Susan Clough, with periodically changing the records so that he could listen to an endless supply of melodies.5

Johnny Cash and his family visited Jimmy Carter’s White House on June 14, 1977. Cash would later team-up with Tom T. Hall to fund-raise for Carter’s 1980 reelection campaign. Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library/NARA

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library/NARAPresident Carter was good friends with many famous musicians, including Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Gregg Allman. He frequently invited them to the White House. Musicians also helped Carter get elected president. During the 1976 election, the Allman Brothers Band, the Marshall Tucker Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Charlie Daniels, Willie Nelson, John Denver, and more held fund-raising concerts for Jimmy Carter. The Carter campaign became a concert promoter, paying the full expenses for numerous performances.6 The profits, backed by matching federal funds, helped make a little-known outsider from Georgia a serious contender for the presidency.7

Yet the relationship between Jimmy Carter and musicians was one of friendship, not political expediency. According to biographer Jonathan Alter, musicians felt an almost mystical connection to Carter.8 He counted performers like Willie Nelson among his closest friends and listened to his music during the Iran hostage crisis to relieve stress.

This photograph of country music icon Willie Nelson kissing First Lady Rosalynn Carter was likely taken in September 1980, during a concert that Nelson performed on the South Lawn of the White House. The First Lady joined Nelson on stage for a duet during the concert. Nelson is an American country music singer and songwriter with a long and storied career of activism for various causes.

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum/NARABob Dylan said of Carter, “He put my mind at ease by not talking down to me and showing me he had a sincere appreciation of the songs I had written.”9 Even when it was politically inconvenient, he was a loyal friend. For example, when Gregg Allman testified in federal court as a witness against his road manager, Scooter Herring, who was on trial for charges related to organized crime, Carter stood by the rockstar when most of his other friends abandoned him.10 He even let First Daughter Amy Carter give Allman a White House tour.11 Carter defended his association with the Allman Brothers by saying, “I’m proud of my relationship with the Allman Brothers Band. They are good people, they are my friends, and anybody who wants a President who doesn’t like music like this, and who doesn’t like people who make music like this, should simply vote for another man.”12

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter also appreciated music as a couple. Both Jimmy and Rosalynn received their musical education from Julia Coleman, their principal and high school teacher in Plains, Georgia. In the 1920s, Coleman studied music, drama, and the arts alongside Eleanor Roosevelt in Lake Chautauqua, New York.13 Miss Coleman taught them to identify classical composers by ear, memorize lyrics, and know by heart the names of concertos and symphonies.14 Jimmy Carter astonished professional musicians like Bob Dylan with his total recall of their song lyrics in part because of this unique education.15

Before using music for diplomacy, Jimmy Carter first used music to help make peace with his son during his Georgia governorship. In the early 1970s, Chip Carter went through a phase of teenage rebellion in which he was not on speaking terms with his father. Their shared love of music bridged the gap between them. The two patched up their generational differences by quoting Bob Dylan back and forth on the telephone. They enjoyed the album “The Times They Are a-Changin.'” The two even met Bob Dylan together!16

This photograph of First Lady Rosalynn Carter listening to her daughter Amy practice the violin in the Center Hall of the Second Floor residence in the White House was taken by Harry Benson.

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum/NARAIf Jimmy and Chip’s experience with music was like peace between warring nations, then Rosalynn and Amy’s experience was like allies working in harmony. In the White House, Amy Carter learned the violin with the help of her mother. Starting in 1977, Amy trained using the Suzuki method. This technique, created by Sinichi Suzuki, models musical education on how babies learn their native language from their parents. Rosalynn and Amy Carter played the violin together and bonded as mother and daughter. Rosalynn enjoyed taking violin lessons with Amy, though she said, “but I don’t have the same touch as well as she does and when I make a mistake, she corrects me.” At the 1978 Suzuki International Children's Festival, Amy performed with two hundred American and Japanese children at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. President Carter and Shinichi Suzuki himself attended, and the president greeted Amy’s fellow performers afterwards backstage.17

Entertainer in Chief

Jimmy Carter benefited from music politically. Rock n’ Roll helped Carter appeal to young voters. In the White House, First Lady Rosalynn Carter organized numerous musical events. They preferred these concerts to cocktail parties with high society.

According to Rosalynn Carter, “If there is one thing Jimmy dislikes more than anything I can think of, it is a cocktail party or reception or dinner every night.”18 Jimmy Carter regularly turned down invitations to dine with more influential figures like Katherine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post. Carter later admitted this was a mistake that contributed to his poor relationship with the press. Yet, he was a Washington outsider. He was determined not to join the establishment.19 Nonetheless, members of Congress, diplomats, administration officials, businesspeople, and more attended his concerts and galas.20 The concerts provided valuable networking opportunities.

Program for Country Music Celebration, April 17, 1978 This event, a celebration of country music, was hosted by President Jimmy Carter in the East Room of the White House on April 17, 1978. Country singers Tom T. Hall, Loretta Lynn, and Conway Twiggy performed at the concert.

Courtesy of Henry & Carole Haller and FamilyHowever, professional conversations and pageantry were not the main point, nor was entertainment for its own sake. The Carters used music to promote harmony, reconciliation, and unity. Just as music was personally meaningful to the Carters, they felt it had value for America and the world as well. He became president in 1977, three years after Watergate and less than a decade after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As president, Jimmy Carter was a firm supporter of the Black community, an early advocate of LGBTQ+ rights, and endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment.21 Carter thought diversity and creativity went hand in hand, saying,

We can have an America that encourages and takes pride in our ethnic diversity, our religious diversity, our cultural diversity—knowing that out of this pluralistic heritage has come the strength and the vitality and the creativity that has made us great and will keep us great.22

Moreover, Carter saw around the world the need for peace. Jimmy Carter used the universal language of music to promote unity and healing, especially in regard to foreign policy and civil rights.

The Symphonics of Statecraft

The Carters saw music as a way to strengthen America’s alliances and promote peaceful diplomacy. Rosalynn Carter believed that “music is a universal language that binds people and nations together.”23 The Carters excelled at using “soft power,” defined as the ability to influence other nations through moral values and culture, rather than threat or force.24

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter greeted opera star Leontyne Price after her concert at the White House on October 8, 1978. It was the first of several noteworthy performances Price gave at the White House during the Carter and Reagan years.

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library & Museum/NARAPerhaps Jimmy Carter’s greatest agent of soft power diplomacy was Leontyne Price. Price is a world-renowned African American opera super-star. She played Cleopatra in the Metropolitan Opera’s Antony and Cleopatra and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. The soprano first performed at the Carter White House on October 8, 1978. Carter wrote of Price in his diary that, “She’s by far the most accomplished singer we’ve ever had.” High praise indeed from a music aficionado like Carter!25

Carter invited Leontyne Price back to the White House on two historic occasions. First, for the banquet that celebrated the Camp David Accords on March 26, 1979. Price performed before President Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of Israel to commemorate their signing of the landmark peace treaty.26 While Carter, Sadat, and Begin forged their treaty by tough negotiations, the ritual of music was an important part of the peacemaking process.

A picture of Leontyne Price singing at the White House during the 1979 White House banquet held in honor of the signing of the Camp David Accords. The soprano would later perform for Princess Diana at the White House during the Reagan Presidency.

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library & Museum/NARAOn October 6, 1979, when Pope John Paul II visited Washington DC, President Carter again invited Leontyne Price to perform. This was the first papal visit to the White House. Carter always strove to do “his very best,” and for this historic occasion, this meant welcoming his holiness with the singer he considered the best in the country, Leontyne Price. Price sang “The Lord’s Prayer” by Malotte and “America the Beautiful” to an audience of 6,000 on the South Lawn. This crowd included the Pope, the president, the nine justices of the Supreme Court, the assembled House and Senate, state governors, and more.27

Jazzy Jimmy

President Carter also used music to promote and celebrate diversity. In 1971, as governor of Georgia, he made national headlines by saying “the time for racial discrimination is over.” He believed the South, and indeed America, could heal from the racism of the past.28 As part of that vision, Carter appreciated and celebrated African-American music for its role in fostering feelings of goodwill and equality.29 In 1979, Rosalynn Carter formed a commission that expanded the White House Record Library to include new sections on soul, blues, and Black gospel. They added these genres to better reflect the cultural accomplishments of African Americans, which the library only represented with jazz albums before.30 Also in 1979, President Carter designated the month of June “African American Music Appreciation Month.”31

This photograph of a jazz concert on the South Lawn of the White House was taken in June 1978 by Donald J. Crump of the National Geographic Service. Renowned composer and jazz pianist Eubie Blake performs on stage while President Jimmy Carter, First Lady Rosalynn Carter and guests look on. Credit: White House Historical Association

White House Historical AssociationOn June 18, 1978, Carter held the first White House concert entirely devoted to jazz, the legendary Newport News Jazz Festival 25th Anniversary concert. More than thirty superstar artists performed for eight hundred people on the White House South Lawn.32 This was not only an entertaining event, but a public political statement supporting diversity and civil rights.

The U.S. often used jazz as a diplomatic tool abroad, but it received less respect at home. In the 1920s, African American jazz musicians traveled as far as Shanghai, China for celebrity and praise they could not find in the United States. Black musicians, accustomed to racism in the U.S., were treated better in China.33 During the Cold War, the United States leveraged the international popularity of jazz to promote American values and to counter Soviet claims that Americans have no culture. America’s first state-sponsored jazz diplomat was Dizzy Gillespie. President Dwight D. Eisenhower hoped Gillespie’s band would show the world that America was making progress on race relations. During this cultural mission, the jazz legend represented the United States in Europe, the Middle East, South Asia, and Latin America.34 It was a great success. Jazz musicians became the face of American diplomacy around the world. Even in the Soviet Union, jazz was massively popular, despite Communist Party efforts to ban it. Duke Ellington caused a sensation when he toured Russia as part of President Richard Nixon's policy of détente.35

On April 29, 1969, Duke Ellington received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Richard Nixon for his contributions to American music, including being a cultural ambassador for the U.S. around the world.

National Archives and Records AdministrationYet within the United States, jazz musicians did not receive the same recognition and respect because of racism. Jimmy Carter wanted to change that. Looking back on the White House jazz festival in his nineties, Jimmy Carter said, “I was deeply infatuated with jazz musicians, so it was a great honor and privilege to bring to the White House these people that in many cases had not been previously recognized for their great contributions to our society.”36

Before the concert, the White House served a buffet supper.37 The Young Tuxedo Brass Band, a marching band from New Orleans, performed. They played “Second Line” and “Bourbon Street Parade.”38

After these energetic tunes, President Carter rose to speak.39 He had just flown back from Panama, where serious negotiations over the fate of the Panama Canal were underway.40 The president showed no signs of stress. He confidently addressed the crowd with First Lady Rosalynn Carter by his side.

At first, this jazz form was not well accepted in respectable circles. I think there was an element of racism perhaps at the beginning, because most of the famous early performers were Black, and particularly in the south to have black and white musicians playing together was not a normal thing. And I believe that this particular form of music---of art---has done as much as anything to break down those barriers and let us live and work and play and make beautiful music together.41

The concert began with a performance by the legendary jazz pianist Eubie Blake. He played “Boogie Woogie Beguine” and “Memories of You.” Then over thirty musicians performed, including Herbie Hancock, Lionel Hampton, Ornette Coleman, Pearl Bailey, Katherine Handy Lewis, Marylou Williams, Roy “Little Jazz” Eldridge, and Dexter Gordon. The songs they performed included “St. Lewis Blues,” “Over the Rainbow,” “In a Mellow Tone” and “Lady Be Good,” “Sonnymoon for Two,” “Caravan,” and “I’ll Remember April.” During the concert, Lionel Hampton renamed his song “Flyin’ Home” “Jimmy Carter Jazz Rag.”42

President Jimmy Carter on stage at a White House jazz concert with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (center) and percussionist Max Roach (right), performing Gillespie's tune "Salt Peanuts. Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum/NARA

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum/NARAAt the end of the festival, Dizzy Gillespie called Jimmy Carter onto the stage. He shared with the crowd that Carter had requested the song, “Salt Peanuts,” but there were “diplomatic strings attached.” With a dramatic flourish, Gillespie said, “To wit that the president himself, his majesty sing the lyrics to ‘Salt Peanuts.’” Carter laughed and obliged.43

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter were life-long lovers of music. As John Chuldenko, their grandson, told Stewart McLaurin, “But music brings them both a lot of joy. You can see it when they dance at weddings. You can see it at home. You can see it in these moments that music plays, and they instantly get up and there’s that light in their eyes. So, it’s no wonder that they would take that love of music into the White House with them.”44 The Carters believed music could build bridges and heal divides. Music enriched their personal lives and was one of the ways they bonded and reconnected with their children. In the White House they hosted concerts featuring every popular genre of the 1970s, from gospel to rock n’ roll. These events served a larger purpose, promoting values like unity, healing, understanding, and inclusion. The performances of Leontyne Price promoted goodwill between the U.S., the Middle East, and the Vatican. The White House Jazz Festival celebrated African-American culture and gave long-overdue recognition to some of America’s most talented cultural ambassadors. Jimmy Carter’s promotion of music is an important part of his presidential legacy.

About the Author

Coleman joined the Association as an intern in May 2024. He is a PhD student at the University of Alabama. He graduated with a BA in history from Emory University in 2015 and a MA with Thesis from the University of North Georgia in 2019. His research interests include Jimmy Carter, the Cold War, and presidential debates. Coleman is from Atlanta, Georgia.