Rubenstein Center Scholarship

“Kitchen Genius”: Dolly Johnson at the White House

“If it is true that men are governed by their stomachs...Dolly... who is to be White House cook, ought to have a big pull on this administration.” -The Old Abe Eagle, March 16, 1893

Cuisine is a central part of life at the White House. From State Dinners and diplomatic receptions to private meals and family events, the White House executive chef and their team feed some of the most influential people in the world. The menus, ingredients, and flavors selected by the culinary staff often convey the personality, taste, budget, and lifestyle of the commander in chief to the public.

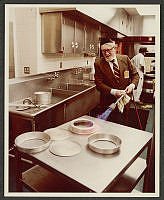

Modern White House kitchen

White House Historical AssociationToday, the White House kitchen staff is robust, including pastry chefs, sous chefs, and part-time assistants, but in the nineteenth century, these responsibilities were primarily managed by a head chef/cook.1 This role has always been extremely important—as Chief Usher Ike Hoover once wrote: “The most respected person in the house other than the President’s immediate family is the cook! All administrations seem to be in awe of [them].”2 This was certainly the case when Hoover joined the White House staff during the Benjamin Harrison administration, and White House Cook Dolly (Dollie) Johnson earned widespread recognition for her delicious Kentucky bluegrass food.3

Dolly’s southern roots heavily influenced her cuisine. She was born into slavery in Georgetown, Kentucky, around 1852 to parents William Johnson and Emily Miller.4 According to newspaper accounts, she was enslaved by Mrs. Jane Miller.5 Unfortunately, there are few documented details about Dolly’s life between her birth and her arrival at the White House, including records related to emancipation. Dolly gave birth to a daughter named Emma in 1866, and in the decades that followed, Johnson catered meals and cooked for the Lexington community.6 By the late 1880s, Dolly cooked for former Union soldier, scholar, and lawyer Colonel John Mason Brown.7

Sources from this period give two possible explanations for Dolly’s hire at the White House in late 1889. Kentucky sources posited that First Lady Caroline Scott Harrison wrote to Lexington resident Mrs. H. M. Skillman and asked her to select a local cook. Skillman was distantly related to the first lady through the Scott family.8 Meanwhile, Washington, D.C. outlets suggested that Civil Service Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt dined at Colonel Brown’s home during a trip to Kentucky and loved Dolly’s food, thus leading to a recommendation for the White House position.9 Roosevelt stated: “I... am ready to testify to the fact that it was one of the best dinners I ever ate. Dollie did herself credit, and the White House could not be better served, I am sure, than it will be by Dollie.”10

1889 depiction of the White House kitchen, published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

White House CollectionIn either case, Dolly moved to Washington, D.C. and joined President Benjamin Harrison’s White House staff in early December 1889, replacing former chef Madame Madeleine Pelouard, who had been fired earlier that year.11 Carp’s Washington posited that: “The President likes the plain dishes of Dolly Johnson, the colored cook he engaged from Kentucky, better than the complicated French menus of her predecessor…in her way Dolly Johnson, too, is an artist.”12 Indeed, newspapers wrote that Pelouard’s “fanciful French cooking was not at all to the plain American taste” of the Harrison family.13 Instead, they preferred Dolly’s bluegrass cooking. This regional cuisine was characterized by savory meats, fried dishes, and delicious breads. She earned $75 per month for her service, paid by the Harrisons.14

Johnson’s warm welcome extended beyond the first family—newspapers reported “there was a great deal of joy among the colored people of Washington over the announcement that a negro cook had been selected for the White House” and that “all the colored employees at the White House are tickled almost to death at the advent of Dollie, who is already a great favorite with them.”15

Jerry Smith also worked in the Harrison White House, and praised the bluegrass cuisine of his colleague, Dolly. He told a reporter that “the introduction of a colored woman from the South into the White House, to preside over its kitchen, would be one of the greatest acts of the president Administration, and add years to the lives of the members of the Executive family.”

Library of CongressPresident Harrison and his family enjoyed regularly scheduled meals prepared by Dolly, eating breakfast at 8:00 a.m., lunch at 1:00 p.m., and dinner at 7:00 p.m. each day.16 The first major meal Dolly made for the Harrison family was Christmas dinner in 1889, about two weeks after her arrival in Washington, D.C. Newspapers across America printed the menu for their readers, “written out for you by the President’s cooks,” which included Blue Point oysters, turkey, and Maryland terrapin, as well as holiday favorites such as mince pie and plum pudding.17

February 1890 menu for cabinet dinner

The Boston Weekly GlobeDolly’s domain included two White House kitchens located on the Ground Floor: one beneath the State Dining Room, used for large events, and one beneath the butler’s pantry for everyday meal preparation.18 There, Dolly prepared meals for important White House guests, including congressmen, cabinet members, and heads of state. She did not do so alone. Mary Robinson, a young African-American cook from Virginia, assisted her in the kitchen. The two made an impressive pair—Dolly managed the basting and roasting of meats and the creation of entrees, while Mary oversaw the making and baking of pastries including crullers, pies, and breads.19

Dolly and Mary illustrated in Pittsburgh Dispatch, June 1890

Pittsburgh DispatchFor approximately seven months, Dolly served as White House cook. However, she returned to Lexington in the summer of 1890 “on account of the protract illness of her daughter,” Emma Bailey.20 After Johnson's departure, another African-American woman named Lucy Branch filled the role. She had previously cooked for the Harrisons at their Cape May cottage.21

In March 1893, when President Grover Cleveland returned to begin his second term at the White House, newspapers reported that White House Steward William Sinclair courted Dolly to return as head cook.22 She cooked gumbo, terrapin, canvasback (duck), and baked opossum for President Cleveland, First Lady Frances Cleveland, and their children.23

The kitchens were vastly different than those she encountered during her first White House tenure. When Dolly first came to the White House, she cooked in infamously run-down rooms. The Ground Floor of the White House was damp, dimly lit, and plagued by various pests.24 First Lady Caroline Harrison wrote in her diary: “The rats have nearly taken the building.”25 As a result, Mrs. Harrison spearheaded a renovation of the kitchens in summer 1892, which resulted in new floors, tiled walls, improved ranges, zinc-lined refrigerators, additional storage space, and fresh coats of paint.26

These changes certainly improved Dolly’s work environment. Johnson also earned $150 per month under Cleveland—double what she had been paid by President Harrison.27 This salary amounts to an impressive $1,800 annually-- the same amount as Cleveland’s male clerks, steward, and chief doorkeeper.28 Nevertheless, her tenure appears to be quite limited, and the details of her departure are unclear. By June 1893, Dolly was reportedly back in Kentucky, working as a cook for Mrs. Whitney and Mrs. Sayre in Lexington.29 Dolly then married Edward Dandridge, a fellow Lexingtonian, in January 1894.30

The woman in the photograph below, taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston in the White House kitchen, has often been identified as Dolly Johnson. However, the Library of Congress dates the photograph “between ca. 1891 to 1893.” It appears to be taken before the 1892 White House renovation, when black and white tile and glass cabinets were added to this kitchen. Realistically, this image could depict Dolly Johnson, Mary Robinson, or possibly another unknown member of the White House kitchen staff in this period.

Library of CongressStill, Dolly maintained relationships with former first families after her return to Kentucky. On March 13, 1901, President Benjamin Harrison passed away, and Dolly sent her condolences to the Harrison family; newspapers recorded that Harrison’s second wife and widow, Mary Dimmick Harrison, was “glad to be remembered by her old friend Dollie Johnson in the time of her great sorrow.”31 In 1906, Dolly sent a pecan cake to the White House for first daughter Alice Roosevelt in celebration of her wedding to Nicholas Longworth.32

Dolly sent a pecan cake to Alice Roosevelt in 1906.

The Interior JournalDolly’s time in the White House also contributed to her success as a restauranteur in Lexington, Kentucky. She continued to cook, opening several dining rooms and cafés in the early 1900s, including one establishment aptly named the White House Café, and catered events for prominent individuals.33 When Dolly died on February 1, 1918, in Lexington, Kentucky, newspapers across the country mourned her passing, celebrating her culinary talents and service to her country.34

Many thanks to Jennifer E. Capps at the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site for her assistance with this research.